As the pandemic moves from phase to phase, the banking sector has seen dramatic swings in public stock valuations and M&A prices. While the volatility of the markets is closely tied to health trends, which remain difficult to predict, a study of the past 18 months provides insights into future community banking performance and value prospects, which can be invaluable for strategic planning in the boardroom and for setting shareholder expectations.

Looking back at 2020, we note the government stimulus response was distinctly beneficial for bank balance sheets (PPP deposits primarily) and income (PPP fee income), not to mention the avoidance of mass nonperforming loans due to forbearance and stimulus. Valuations for public banks showed the uncertainty playing out with initial precipitous declines in bank stock prices through the early phase of the pandemic followed by a dramatic recovery in bank stocks (along with most consumer-related companies) after the vaccine efficacy announcements. As we turn now to the latter part of 2021, there is much to digest in order to set expectations about the months ahead.

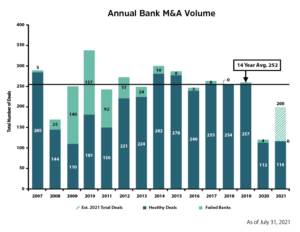

It was no surprise that bank M&A volume dropped in 2020 to less than half of its 14-year average. Understandable as most banks spent a large portion of the year focused on survival, staff and customer health, and contingency planning. Given that the normal drivers of community bank M&A such as succession issues among management/boards/shareholders did not pause for the pandemic, we knew to expect pent-up demand for M&A after such a drop in activity. So far, 2021 has seen a resurgence in M&A, but primarily among the larger bank sellers taking the now-recovered stocks of large buyers. Compounded by the political landscape and tax/regulatory implications of a new presidential administration, M&A volume can be expected to continue its acceleration.

Buyers using cash represent a smaller portion of overall M&A activity recently than we’ve seen historically. So far in 2021, only 33 percent of transactions have been all-cash compared to a 10-year average of 50 percent. Clearly stock buyers have a hot hand to play given the rebound in stock prices, but another difference between acquisitions financed with cash versus stock is having an impact: With stock transactions, the seller is issuing new shares and thus bolstering its capital, so the deal becomes partially self-financing. Not so with cash buyers, unless they choose to raise debt or equity funds on the side. Critically, the availability of excess capital has been whipsawed in recent quarters.

Buyers using cash represent a smaller portion of overall M&A activity recently than we’ve seen historically. So far in 2021, only 33 percent of transactions have been all-cash compared to a 10-year average of 50 percent. Clearly stock buyers have a hot hand to play given the rebound in stock prices, but another difference between acquisitions financed with cash versus stock is having an impact: With stock transactions, the seller is issuing new shares and thus bolstering its capital, so the deal becomes partially self-financing. Not so with cash buyers, unless they choose to raise debt or equity funds on the side. Critically, the availability of excess capital has been whipsawed in recent quarters.

Consider the plight of a bank that relies on cash to fund its acquisitions. Like most banks, they’ve experienced tremendous balance sheet growth in a short period of time which in many cases has stressed their capital levels. On an annualized basis, deposits and loans grew more than 30 percent in the second quarter of 2020 as government stimulus, i.e. liquidity in many cases without a use, cascaded onto the balance sheets of financial institutions of all stripes. Without as much excess capital, there is less ability to use cash for acquisitions without external financing.

Another concern likely on the minds of all buyers but one that might impact those relying on cash for acquisitions more prominently: How much of a seller’s current balance sheet and income are artificially increased by the government’s stimulus response, and will asset quality become an inherited problem post-acquisition once the economy (and retail businesses in particular) are left to stand on their own? To be sure, stock buyers may share this concern but using stock is more about relative values, using cash permanently sets the valuation for better or worse.

Regardless of whether we assume cash transactions will be slower to rebound, we can say with certainty that the consolidation of the banking industry remains acute. De novo charters have not increased though more bank charter applications are currently pending than in prior years. Unless new charters increase from less than 10 per year as we’ve seen all but one year since 2010, to something closer to the norms before the Great Recession when 100 new charters in a year was common, we’ll continue to see dramatically fewer banks across the nation as a result of M&A activity.

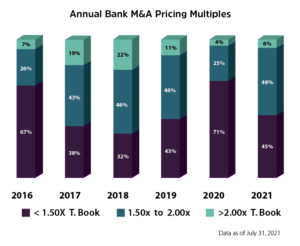

Pricing trends for overall bank M&A activity have followed the public stock trends for banks. Case in point: The most aggressive M&A pricing in the industry matches the 2018 peak of tangible book multiples for public bank stocks, then weakened in both 2019 and 2020 but has recovered in 2021 to levels similar to 2019. The chart below shows the portion of bank M&A announcements by year that fell within three categories of multiple to tangible book: Less than 1.5x, 1.5x to 2x, and over 2x.

As with many performance metrics in the banking industry, size has a strong correlation to higher M&A prices. In 2018-19, banks with between $1 billion and $5 billion in assets that sold received a median price to tangible book multiple of 1.95x while banks with less than $100 million in assets received a median 1.30x (33 percent lower) and banks with between $100 million and $500 million received a median 1.59x (18 percent lower).

Not coincidentally, the $1 billion to $5 billion group was most likely to be taking a buyer’s stock during a peak market for public equity values. During 2020, the pandemic was a great equalizer, essentially removing the price premium for larger banks for the few transactions that were announced (the 33 percent and 18 percent discounts mentioned above had decreased to 10 percent and 1 percent, respectively). The size premium has returned in 2021 with a median 1.25x (26 percent discount) for the banks under $100 million and a median 1.32x (22 percent discount) for banks between $100 million and $500 million compared to the $1 billion to $5 billion group at 1.69x tangible book.

Not coincidentally, the $1 billion to $5 billion group was most likely to be taking a buyer’s stock during a peak market for public equity values. During 2020, the pandemic was a great equalizer, essentially removing the price premium for larger banks for the few transactions that were announced (the 33 percent and 18 percent discounts mentioned above had decreased to 10 percent and 1 percent, respectively). The size premium has returned in 2021 with a median 1.25x (26 percent discount) for the banks under $100 million and a median 1.32x (22 percent discount) for banks between $100 million and $500 million compared to the $1 billion to $5 billion group at 1.69x tangible book.

Finally, we see a marked difference in 2021 with the median size of the buyer. Since 2010, the median size of the buyer in bank M&A transactions had grown gradually from $705 million in assets to $1.6 billion in 2019. Undoubtedly this reflects two trends: The growth of all banks in an industry marked by increasing aggregate assets but decreasing number of institutions, along with the ever-strengthening stock market for bank stocks during that period (pulling more large banks into M&A).

Once the stock market retreated in the early stages of the pandemic, the median buyer size dropped to $784 million in 2020 as larger banks lost their deal-making currency for most of the year. As mentioned previously, when efficacy rates of the newly-developed vaccines were announced last November, bank stocks appreciated rapidly and larger banks began acquiring as evidenced by the record median asset size of buyers so far in 2021: $3.3 billion. Of note, the median seller size has been less volatile but followed the same trend, growing steadily from $116 million in 2010 to $206 million in 2019, retreating to $125 million in 2020, but increasing to $369 million so far in 2021.

The type of buyer for banks has been fairly steady. By far the most common buyer is another bank, but investor groups represented 13 percent of all bank buyers in deals announced so far in 2021. This compares to 11 percent in 2020, 10 percent in 2019 and 12 percent in 2018. Undoubtedly many of these investors would have applied for de novo charters in prior decades, but given today’s climate for new charters and increased capital requirements, acquiring a small bank can be a faster and less expensive path.

Meanwhile credit unions as bank acquirers had been a fast-growing trend since 2015 but has leveled off since 2019. In 2018, credit unions represented 3 percent of bank M&A deals each year, peaking at 6 percent in 2019, then 5 percent for 2020 and 5 percent so far in 2021. Any increase in corporate taxes will only magnify the advantages of credit unions, potentially enhancing their ability to pay a more attractive price than banks can justify.

As we complete 2021 and look ahead to 2022, we must acknowledge that uncertainties abound when it comes to planning for the future. Among the uncertainties are the pandemic health trends, tax/regulator/political landscape, interest rate environment, and bank asset quality trends.

We might expect another retreat from M&A volume and prices if the public market for bank stocks declines, otherwise expect public banks to seek growth aggressively by using their stocks as currency, often allowing the seller to qualify for a tax-free exchange (more appealing as tax rates increase). At some point the activity level of smaller banks buying and selling will likely increase as cash buyers get comfortable with their capital levels and trust the financial trends of sellers.

John Adams is head of investment banking for Sheshunoff & Co., Austin, Texas. You can reach him at [email protected]. He is participating in the Bank Holding Company Association’s Fall Seminar to discuss M&A trends and talk about how banks can build shareholder value. Learn more on the BHCA website.