Leader of Minnesota bank is making an impact at the local, state and federal levels

Editor’s note: Our thanks go to Bell Bank, which sponsors the Banker of the Year program.

Suing your regulator is a bold step many bankers would hesitate to take. It certainly wasn’t a flippant choice for Bryan Bruns, president and CEO of Lake Central Bank in Annandale, Minn. But that’s exactly what he and the bank chose to do last summer, when they joined the Minnesota Bankers Association in a suit against the FDIC over recent guidance the agency issued requiring banks to retroactively evaluate their non-sufficient funds policies.

“A lot of agencies are implementing changes with a microphone rather than through the appropriate procedures,” Bruns said. “It’s not really about the fees; it’s about the process. I don’t think they followed the process, and in this case at least, I don’t think they have the authority to do this to begin with.”

For Bruns, it’s a simple matter of fairness and following the written rules, which ought to apply to everyone. His willingness to step into the spotlight and back his words with actions has drawn praise locally and nationally.

“That’s not an insignificant decision,” said Rob Nichols, president and CEO of the American Bankers Association. “It’s a tangible example of him taking on leadership on a national level.”

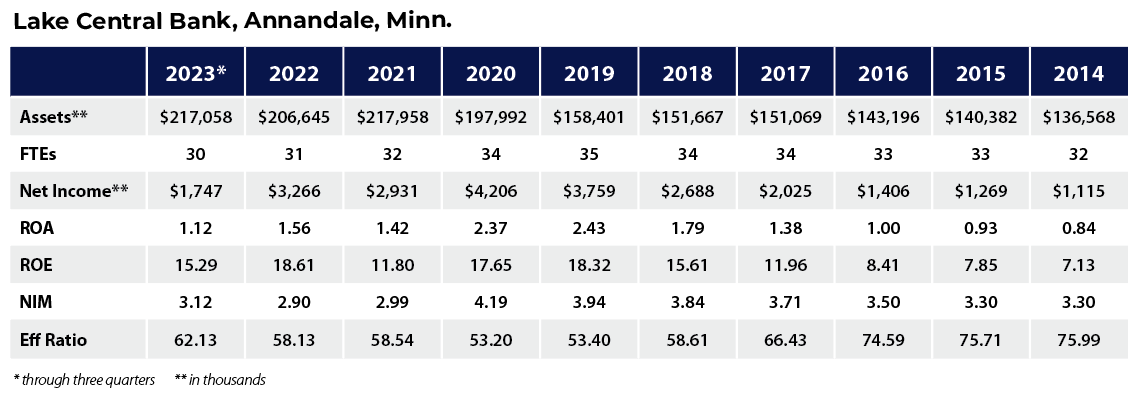

Bruns has built to that national presence through decades of growth and work in the community banking basics at his $217 million institution about an hour northwest of Minneapolis. His care for the daily work of banking at Lake Central has influenced his passion for industry advocacy and desire for the industry to remain strong for all players.

“Suing your primary regulator is not something an organization’s really excited to ever do,” said Tony Moch, an attorney in the community banking practice of Minneapolis firm Winthrop & Weinstine who’s worked with Bruns since 2010. “He did it from an industry perspective of, ‘I really think that what we’re doing is the right thing to do for community banks, and if that means I have to take a stand, then so be it.’ He was willing to do that.”

For his advocacy work building up the industry at the local, state and national levels as well as his thoughtful, deliberate dedication to the essence of community banking, Bryan Bruns has been selected as BankBeat magazine’s 2024 Banker of the Year.

Improving the industry

Bruns got his early start in association involvement via the power of example. His father — and predecessor at the helm of Lake Central — Dwayne Bruns had held the chair’s gavel at the Minnesota Bankers Association in 1993-94; almost two decades later at the tail end of the Great Recession, Bryan would follow in his father’s footsteps.

As regulators grappled with the crisis fallout, a raft of reforms were enacted, including the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. While its goal of helping protect consumers was understandable, said MBA President/CEO Joe Witt, bankers were caught in the backwash of unintended consequences and regulatory overreach amid the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “That was a tough time when we had politicians and everybody blaming everything on the banks,” Witt said. Dodd-Frank proved to be one of the most challenging parts of Witt’s 27 years at MBA. Bruns helped provide a guiding hand amid the turmoil.

Witt estimated that he first met Bruns on one of the association’s regular trips to Washington, D.C., and the latter has continued his dedication to policy efforts on the national as well as state stage.

After observing the immediate impact of the CFPB’s creation, Bruns joined its community bank advisory board in 2018 for a one-year term when former congressman Mick Mulvaney was serving as acting director. At the time, the agency had three advisory boards representing different groups of stakeholders. They had met independently but never interacted as a large group, something Mulvaney rectified. Bruns praised his decision: “That’s just common sense to me.”

Also in 2018, Bruns brought his analytical skills to bear for the ABA on its Core Platforms Committee. It’s the rare banker who is truly happy with their core processor, and the committee members were tasked with finding a better way forward. The group brought together the two sides — core user and core provider — to hash out pain points and technology limitations. Bruns was right at home at the table as the debates unfolded.

His own experience going through a core conversion earlier that decade proved illuminating. Lake Central had switched from hosting everything onsite in its facility to outsourcing it to a data center as technology requirements became more complex. Bruns dug into their provider’s offerings, comparing them to other vendors’ before selecting a different partner who provided a better fit. “If you don’t take the lead on a core conversion and push it through, it can blow up real quick,” he said. “Because I had gone through some conversions in my previous working career, I wasn’t afraid to do that.” But Bruns made sure his staff was on board with the change and ready to implement the new tech as a unified team.

He joined the ABA’s Community Bankers Council in the mid-2010s, eventually moving through its executive committee. He co-chaired its annual conference virtually in 2021 and chaired it solo as it returned to an in-person gathering in 2022. During the pandemic, Bruns brought his voice to government leaders as they grappled with the unfolding crisis. “We got to hear directly from the Small Business Administration, from the Treasury Secretary,” he said. “They were on Zoom calls with us to make sure that we were responding to the American people’s financial needs.”

He currently is serving the final year of a three-year term on the ABA board. The FDIC lawsuit is the latest chapter of his advocacy work.

“It’s sometimes hard to keep up because obviously he’s in the thick of it and wears a lot of hats and is up to date with the politics at the national level and state level and regulatory level,” said Pat Eastman, Lake Central’s board chair. “It’s pretty amazing. Sometimes it’s all we can do to gently remind him to slow down or leave a little time for himself. It’s really an education working with him.”

Building by dialogue

Bruns is a true believer in getting disparate voices around the table to talk things out, whether it’s the board room in Annandale or the halls of power in Washington. It’s part of what drew him to become so heavily involved with MBA and then ABA.

“I liked being involved in organizations where all voices were represented and could come together and debate before presenting a unified front,” he said. “For me, I like that the largest banks in the country and the smallest banks in the country are in the same room discussing what’s best for the industry. We definitely don’t agree on everything, but we agree on way more than we don’t.”

When he became MBA chair in 2012, Bruns emphasized the importance of outreach to legislators and regulators. “If a banker is not involved in the political process then in my mind he or she is crossing their fingers and praying that the politicians will magically understand the issues that affect us,” he declared in his speech at the convention that year.

Bruns has made it a goal to get various stakeholders into the same room to hash out differences, find common ground or simply to exchange viewpoints. He’s prioritized it across his career, bringing elected officials — including U.S. Rep. Tom Emmer, who sits on the House Financial Services Committee — into Lake Central to demonstrate loan closings and the practical impact of regulations and legislation on the average consumer.

“[Bruns is] a wonderful ambassador for the sector and a stellar participant in all of our deliberations,” Nichols said.

Multiple people, including Nichols, cited Bruns’ work with ABA’s Core Platforms Committee as an example of both his dedication to dialogue and what is possible to achieve through it.

“The smaller banks feel like they don’t have a lot of power to negotiate with the core processors,” Witt said. “I think the project that they did was hugely important, and I think it’s made some real strides in making that relationship a little bit more evenly matched by bringing those people to the table.”

Bruns’ work on the committee interviewing dozens of providers helped lead to the establishment of standards and guidelines for bank-core provider relationships.

Family partnership

Grade school classmates knew Bryan Bruns was destined for the banker’s desk. A former classmate — now an electrician, still a Lake Central customer — once told an anecdote about the youthful Bruns: They knew he’d follow in his father’s footsteps because even in fourth grade he had a banker’s haircut, a banker’s wardrobe and most importantly, a banker’s temperament. Having a fondness for numbers and an analytical mind, Bruns pursued a degree in finance at the University of Minnesota.

Dwayne sent Bryan out of what was then Annandale State Bank to seek experience elsewhere. The younger Bruns landed an internship at Norwest Bank (now Wells Fargo). He moved on to a position at Marquette National Bank (now part of U.S. Bank), where he leveraged a willingness to tackle any project thrown his way. It was the early days of email, and Marquette executives weren’t enthralled by the new tech. Bruns volunteered to learn the ropes and help implement it, starting with more tangential uses until staff was comfortable. He trekked to different branches to perform internal audits — at the time, many existing as their own charters under the Marquette umbrella — to observe best practices at each with an eye to improving processes at all. He also spent time working on mergers and acquisitions.

He was invited back to the bank his father ran in the early 1990s to take over as cashier. Initially, Bruns was unenthusiastic about the idea. His star was on the rise at the larger bank, and he didn’t want to derail it. A call from the board chair, revealing that they were looking for a successor for his father down the road, ultimately drew him back to Annandale.

The partnership with his father proved a complementary one: Dwayne was quick and decisive in his planning while Bryan favored a slower, thoroughly researched approach. “I knew I could be honest with him,” Bruns said, and they’d hash out any disagreements about strategy or process. He’s ensured that he’s still surrounded by team members who pair well with his strengths over the years to continue that foundation. He became president of the bank in 2005 as part of the transition, adding the CEO role when Dwayne passed away from pancreatic cancer in 2014.

Bryan Bruns’ eye for detail and keen memory have proved useful in other ways, said Keith Jerpseth, Lake Central’s head lender. More than three decades after he left Marquette, Bruns recalled the ways in which the large bank had arranged some backend infrastructure and applied it to the State Bank of Danvers, easing integration of the bank after it was acquired by Lake Central Bank last summer.

Like many community bankers’ children, Bruns grew up pitching in on small tasks around the bank, mowing lawns and shoveling sidewalks. In high school, he moved up to the teller line. As he watched the professionals around him, however, the young Bruns noticed their interactions with the community members. The tight-knit relationships became an ideal for him, and he’s worked hard to ensure that same closeness and personal service continue even as much of banking’s basics move online.

“Bryan understands community banking,” said Steve Niklaus, who’s been on the Lake Central board for 20 years. “He understands it very well and what it represents and what it stands for and the value of community banking for the overall health of the community. He practices that on a regular daily basis as CEO at the bank.”

The pair spent time on the school board together, Niklaus as superintendent for 25 years and Bruns as a member for a dozen years. It’s one of many ways Bruns has given back to Annandale over the years.

Looking to the future

Community bankers must balance the close personal relationships they’re known for with integration of the latest tech offerings, Bruns said. The core principles of the industry haven’t changed much, even as bankers wrestle with the current challenges of high rates and cost of funds, but they can’t ignore the realities of customer expectations.

“Being able to stay relevant today is to still have those connections with your community,” he said. “But you need to be putting in technological advances in your bank, or those customers are not going to have any choice but to leave you because they need convenience.”

The pandemic accelerated some of those trends, notably the shift to digital channels and embrace of technological tools. But underneath those changes, people still crave the personal connection they find from being in the same room to conduct business, Bruns said.

“Another part of his leadership that really stands out is Bryan is willing to move banking into the future,” Niklaus said. “He understands the technology that has become part of people’s lives, and is willing to incorporate that into the bank.”

But you can’t chase change for its own sake, Bruns believes.

“I encourage my staff to be constantly thinking about innovation and constantly be thinking about not just change for change, but change for a better process,” he said.

Annandale is a good illustration of the pandemic shifts and broader changes in the industry. The population has more than doubled since Bruns was in school, now standing just under 3,500. It’s gone from a more heavily rural area to being sandwiched between the stretching urban sprawl of the Twin Cities and St. Cloud.

Its lakes have always drawn a crowd of city dwellers who borrowed from the bank to build vacation homes and weekend getaways. The pandemic pushed more remote workers to the charms of its small-town attractions, and some have stayed as locals debate the merits of creating a coworking space in town.

Bruns’ beliefs about the importance of in-person dialogue contribute to his opinion that the current work-from-home movement is on the ebb. The bank has a focus in real estate, but this far outside Minneapolis’ downtown core, the CRE is mostly owner-occupied. Its acquisition of State Bank of Danvers in August 2023 was motivated at least in part by portfolio diversification: Lake Central doesn’t do much ag lending, while State Bank of Danvers does.

“He’s thoughtful about what happens going forward with his bank, not just from an acquisition standpoint, but because he does believe it’s important to the community, and continuing to ensure that the bank’s going to be there longterm,” said Moch, the attorney who worked with Bruns to form Lake Central’s holding company in 2010. “That means being thoughtful about the next generation. How do you bring along the next group of bankers and how do you help them and mentor them? And I think he’s got some good examples of up-and-coming folks at his organization.”

That next cohort of talent includes Bruns’ daughter and son-in-law who work at Lake Central after starting their careers at other institutions.

Bruns has made it his mission to ensure that community banking will be around for generations to come, both in his industry-level campaigning and his contributions at Lake Central and in Annandale.

“I have been told for years, if you are not involved in the discussion then you shouldn’t complain about the outcome,” he said in his 2012 speech as MBA chair. “I believe if we are not involved in the discussion we may no longer have an industry to complain about.”

Thanks to his work across the breadth of community banking, from his single institution to the associations that lobby for them, Bruns is doing everything he can to make sure those discussions continue to yield abundant fruit.