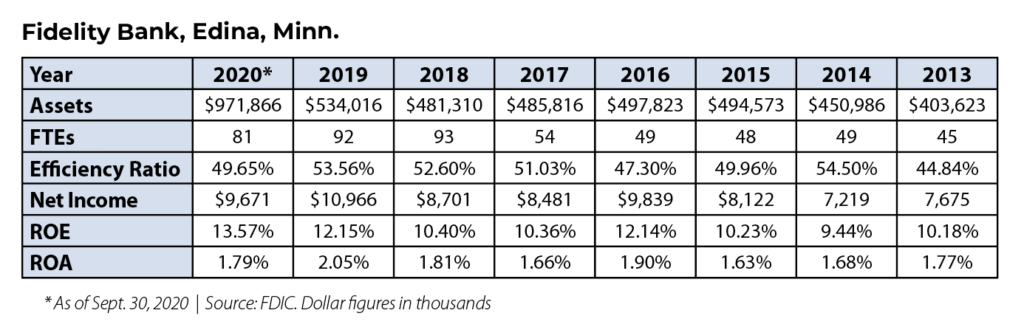

As 2020 neared its conclusion, Fidelity Bank, was on track to rack up more business than during any other year in its 50-year history. When year-end numbers are posted, it is likely the bank will have doubled in asset size from 2019, and quadrupled its warehouse mortgage lending volume.

To understand how the $770 million Edina, Minn.-based commercial bank posted such noteworthy performance this past year, one must travel back in time to the early days of the Great Recession, when as the newly-minted president and CEO, Chuck Mueller faced a pivotal question about whether the bank should stay active in warehouse mortgage lending when the housing market across the country was in freefall and independent mortgage companies were vanishing.

Adding weight to Mueller’s decision-making were earnings expectations from new owners who’d acquired Fidelity in 2005 — at the top of the market.

“Good timing, right?” Mueller laughed. Age softens even the harshest memories.

Mueller, who isn’t attention-seeking and considers himself “quietly competitive,” had always worked on the commercial lending side of the business. He had mastered the art of short-term, asset-based lending, and was adept at guiding his lenders and young analysts in ways to demonstrate to commercial clients the value of a working capital loan.

Warehouse mortgage lending had been a colleague’s baby, and that person had been on track to earn the chair which instead became Mueller’s on the first day of 2008.

The actions Mueller took in the midst of that financial crisis not only kept the bank in warehouse mortgage lending but also positioned it to respond when the market rebounded. In the dozen years Mueller has led Fidelity, the bank has diversified within its niche, shored up its foundational service to small- and mid-size businesses, and mastered the challenge that dogs many closely-held companies: Growing its next-gen leadership.

In a career that spans 38 years, Chuck Mueller has made a positive and lasting mark on Fidelity Bank. Mueller is BankBeat magazine’s 2021 “Banker of the Year.”

Cementing the niche

In 2020, Americans took full advantage of historically low rates to either buy a home or refinance their mortgage. Freddie Mac forecasted that by year-end 2020, purchase originations would total $1.414 trillion and refinance originations would total $2.168 trillion. Roughly half of those originations would be completed by nonbank mortgage lenders using warehouse lines of credit.

This was not the case in 2007, when nonbanks originated approximately 20 percent of all mortgages. The subsequent housing crash, which took a lot of banks down, also brought an end to many nonbank mortgage originators. According to the Brookings Institute, the total number of mortgage companies fell by half between 2006 and 2012. Some closed their doors while others, such as Bell Mortgage, were absorbed by banks. A noticeable number of those companies were customers of Fidelity Bank.

Mueller joined Fidelity in 1983 as a commercial lender, attracted to the type of lending the bank engaged in: Working capital lending, short-term notes secured by business assets. “Most banks at that time, it was two-to-one debt-to-equity, a couple of years in business, otherwise, come back and see us later,” he said of 1980s-style commercial lending. He saw the value in that type of loan but it didn’t energize him to pursue those types of deals. “This bank stood out because it really had an identified niche” of short-term, asset-based and accounts receivable lending.

Mueller found his bliss at Fidelity, energized by the variabilities of working capital lending. “When you walk in the door, you never know what you’re going to be dealing with and that scares some people,” Mueller said. “There’re concentration issues, fluctuations in the economy, opportunities or problems, and you don’t know when your customer is going to get paid or not get paid. You really have to be on your toes.”

Fidelity mostly steers clear of long-term commercial real estate lending, but has what Mueller deemed a “clean-as-a-whistle” $85 million CRE portfolio of owner-occupied properties with good loan-to-value ratios. Like many of its peers, it was busy last spring processing Paycheck Protection Program loans. But unlike many of the community banks in its class, Fidelity doesn’t lend into agriculture and it has zero retail customers. It doesn’t even own its building, operating for all of its 50 years in leased offices in the nondescript, 1960s-era Pentagon Park.

The bank got into mortgage warehouse lending in the late 1980s through fellow Fidelity banker, Andy Feriancek, when a client in “the Park” was seeking mortgage origination funding. “It was Andy’s baby,” Mueller said.

Mortgage warehouse lenders extend lines of credit to mortgage originators to fund home loans, with the intent that those loans will be quickly sold into the secondary market and the warehouse lender will be paid back. Fidelity holds the mortgage note as collateral until the loan is sold. Sometimes, Fidelity makes a short-term purchase of the mortgage from the originator, but it will sell it back before the mortgage company sells the loan downstream. Fidelity never packages and sells mortgages.

Feriancek was Mueller’s supervisor and executive vice president. “He gave me a lot of latitude to succeed or fail, to develop the team,” Mueller said. Call it trust; it was what kept Mueller at the bank.

Feriancek was the person poised to follow Jim Morton as the next president and CEO, and Mueller was content in his focus on developing the commercial lending team, “building the structure and the systems for success,” including mentoring the new hires, fresh out of college, an activity Mueller said he relished.

Todd Williams, current bank president and one of Mueller’s hires, said Mueller understands the personal side of the business. “You have to be somewhat of an advocate and a trusted person for that business owner,” Williams said. “He did a good job of teaching the talent that he has, which afforded us the ability to do the things we’re doing now.”

One of Mueller’s defining contributions to the bank, Williams said, was mentoring. “He really enjoys people who have inquisitive minds.”

Mueller feeds on developing young talent, added Teri Keegan, chief financial officer. “His influence is in growing talent,” she said. “He’s also very comfortable with ambiguity.”

Both Williams and Keegan said Mueller excels under pressure, even performs best under stress. His actions in 2008 illustrate this, yet his penchant for leadership coalesced earlier, back in June 2002. That was when 54-year-old Feriancek went to play a round of golf and suffered a fatal heart attack right there on the golf course.

The vote of confidence

The loss of Feriancek was substantial, both in terms of the grief one feels when a colleague of 20-plus years is suddenly gone, and its impact on succession. Morton had been the longtime leader of Fidelity and Mueller considered him the “quintessential community bank president” because of Morton’s friendly, outgoing nature. But Morton hadn’t kept a deep management bench.

When his grief abated, Morton turned his attention toward Mueller.

“There was no question he was going to be the next guy,” said Morton, who is retired and living in Florida. “Chuck did a great job with customers. He got close to them, helped them understand the ways they could grow their businesses.”

When it became clear to Mueller that he was the new heir, he and Morton moved to build a management team. They hired Keegan, who had helped launch a credit union; they promoted Williams to fill Mueller’s shoes as head of commercial lending, and hired Steve Stoup as head of marketing and business development. (Stoup no longer works at Fidelity.) The team gelled.

Fidelity opened its doors in 1970 as Southwest Fidelity Bank of Edina. The bank changed owners in 1986 and again in 2005, when a trust controlled by the Rauenhorst family, which owns commercial real estate developer Opus, acquired the bank. The 2005 acquisition was pure investment; the owners made it clear they were in it for the earnings and would stay hands-off operationally.

The sun shone brightly on them all during that first year. “Then the wheels started coming off the cart,” Mueller said. Populating the board, in addition to Mueller and Morton, were Keith Bednarowski, chair of Opus, William Queenan, chief credit officer of Wells Fargo, Phillip Goldman, who had been with the World Bank, and R. Craig Flom, who is current board chair. “Very talented business people,” Mueller said.

The board met monthly through the worst of the crisis. “They gave us a free hand to work through it completely. And when you think about putting that kind of money into an investment and giving that kind of latitude, it’s the best vote of confidence you could possibly have from owners,” Mueller said. “That was a real learning experience for me going through that severe downturn, but then working with the talent that they provided on the board.”

The clean-up

The trendline for mortgage lending was heading south as Mueller became president and CEO. “We were losing clients,” said Keegan, who recalled discussions centering around whether Fidelity should abandon mortgage warehouse lending. “Chuck had to really learn the business, and when he did, he saw that some of our processes weren’t as solid as they needed to be.”

Mueller said he knew the business “in concept.” When he dug deeper he discovered “less than stellar product.” The bank absorbed some hits in 2008 and 2009. At the same time, Mueller took his objective eye to the program, which he distills as “just short-term receivable” lending. “I had no preconceived [notions]; I could look at it with the eyes of an outsider and look at the pros and cons,” he said.

“When Chuck took the reins, he wanted to do a top-down review so [the bank] could respond to the unique economic circumstances of the moment,” said Peter Stein, an attorney with the law firm of Gislason and Hunter. Stein had his own firm then and had been working with Fidelity for years prior to the crisis. The review Stein and Mueller undertook was “far and away the most significant project I worked on in my career,” Stein said.

The legal team read every reported decision on anything that touched on warehouse funding and rewrote every document from scratch based on those decisions, Stein said. “There are issues you have to address to make sure you are listed as the one owner of that mortgage so nobody else has the rights to that mortgage,” he explained.

It was critical for the bank to keep loans flowing and to ensure each one was perfect. “That’s the kind of detail you have to design, so it’s efficient and effective, so you can prove it,” Stein continued. The process took more than a year, and remains ongoing because regulations are fluid.

“Fidelity plays in a big playground,” Stein said. “Most of its competitors are very big boys. To be as successful as it has been, it has to assess and provide for risks in ways that the big boys don’t have to, because of their size.”

When you rank the nation’s top mortgage warehouse lenders, by commitment, you will find the depository institutions you would expect: JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, U.S. Bancorp, BB&T, Comerica. And then you will find, at roughly No. 15, Fidelity Bank.

“Chuck was a good leader in the sense that he kept focused on the task,” Stein said. “All of us were keenly aware of the unique economic crisis we were facing. All of us were scared, but Chuck has a good ability to project confidence.”

It wasn’t just his team who needed to feel Mueller’s confidence. So did the board and the bank’s regulators. They all got from Mueller what they needed.

Stein also credits Mueller with having the unique ability to focus simultaneously on the big picture and the minutiae. “That allowed us, under his direction, to develop a program that was not only appropriate for the crisis situation of 2008, but one that would give the bank the capacity to grow,” Stein said.

Once the bank worked through its issues in 2009, it found that many warehouse lenders had left the business. “This afforded us a huge opportunity,” Mueller said. “We had our new owner’s backing, we had the capital to support us, the bank had the capital on its balance sheet to do it, and we got opportunities from all over the country.”

Fidelity extended warehouse lines to a company in Madison, Wis., which led to expansion throughout the Midwest. In 2014, it purchased a warehouse operation in Houston that served small and start-up mortgage originators. The mortgage landscape has since evolved with nonbank originators commanding more than half the market today.

In 2020, Fidelity’s warehouse lending volume soared. Its September 2020 volume was four times larger than the same period in 2019. As the year came to an end, Fidelity was on track to process and fund $7 billion in mortgage warehouse volume. “It’s the gift that just keeps on giving,” Mueller said.

A different flavor

Mueller grew up in Bonduel, Wis., situated just outside of Green Bay. He was a youngster during the Vince Lombardi era, when the Green Bay Packers won five championships under their legendary coach. Mueller maintains his allegiance to the green-and-gold, though he’s been a Minnesotan for more than half of his life.

Mueller’s father, Charles, was a life-long community banker at the State Bank of Bonduel. In an interview published in 2008, Mueller said his father insisted his mother shop at all three grocery stores in town because all three shop-owners were his customers. Mueller said his father had the highest degree of integrity. “He would always make decisions that were the best for the community.”

Mueller earned a business degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the 1970s. After graduation, Mueller was hired as a credit manager at the First American National Bank, a mid-sized bank serving central Wisconsin. The bank put Mueller through its training program, where he learned retail banking, worked as a commercial lender, and even did a short stint as a correspondent lender. “It was a real good career start, though I didn’t know it at the time,” Mueller reflected.

Believing he had a foundation to succeed at a larger bank by 1982, Mueller took a job at M&I Bank in Racine, Wis. The move would put him in proximity to Milwaukee, where he had friends and a sense of belonging from his college days. But the leap to M&I demonstrated he hadn’t yet honed his situational awareness. “I was miserable down there,” he said. “I think I did two loans in six months.”

After a lunch with his supervisor to discuss his future, Mueller learned he wouldn’t have one at M&I. Mueller interviewed with Morton and Feriancek at Fidelity a month later. “I’d never been to Minneapolis before, but I needed a job.”

The move to Fidelity from M&I, to a bank with one office compared to the largest bank in Wisconsin operating hundreds of branches, helped Mueller see he preferred “a smaller organization with flexibility; that’s always been given to me here.”

A few years later, Mueller left Fidelity for a loan workout position at Norwest, now Wells Fargo. He was less than one week in when he realized he’d made a mistake. “I called Jim Morton and asked for my job back.”

Morton said yes.

“I really owe him a lot for that,” Mueller said.

Mueller is quick to credit his mentors — and his mentees — for the success of the organization. Kelli Starkey and Susan Johnson have been crucial to the development of the warehouse lending business, he said. Williams was instrumental in the bank’s decision to buy the factoring business, TCI Capital, in 2018, which widens the bank’s reach in the realm of accounts receivable lending by deploying the same skill set that allowed the bank to master warehouse lending.

“I think we recognize that Fidelity has a different flavor than other banks,” Williams said. “It’s a very intensive type of lending, and generally bankers from larger banks or from community banks come in and they aren’t a good fit.

“Plus you have to be really, really close to your customers,” Williams added. “You have to trust them and they have to trust you.”

Williams joined Fidelity in 1987 and has parlayed his opportunity to work with and learn from Mueller all the way to the top of the organization. Williams was named company president last July, giving the reflective Mueller the latitude to focus on strategy and the people he thinks of as his family. His focus on people is illustrated in his commitment to flattening the org chart, and investing in communications and culture initiatives to continually respond to their needs.

“You know, if you hold onto people and you treat people right, you treat people with respect, it pays dividends, it pays dividends, it pays dividends,” Mueller said. “I don’t know anybody who wouldn’t like that.”