No matter the market, a bank today likely has competitors offering 5.5 percent on a certificate of deposit. With competitors pushing the pricing envelope, leaders certainly may wonder: Will high cost of funds become a threat to return on assets?

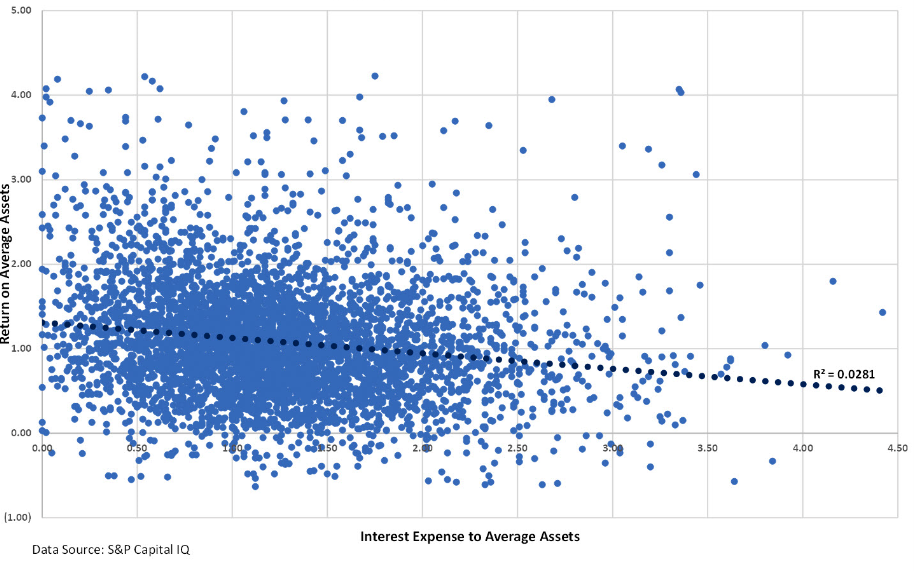

It might comfort — and surprise — bankers to know: There’s a low correlation between low cost of funds and high return on assets. In fact, the correlation is so low that one cannot be used to predict the other.

That may sound like banking heresy, but only recent rate history makes it seem so. If you asked a banker in 2003 if low cost of funds equated to high ROA, he’d have told you that low funding costs are necessary for high profitability. They are necessary, but they are not sufficient for it.

It’s similar to a used car lot owner who’s buying inventory. They can offer sellers low prices, thinking the risk is only in paying too much. But if offers are too unfavorable to buyers, the business may not gather sufficient inventory to fund operations. It’s about paying the lowest price and acquiring the most vehicles.

Even with the most charming salespeople in the world, profit is still dependent upon both price and volume. Rate conditions today are forcing banks to get good again at the balance between them.

The squeeze is on

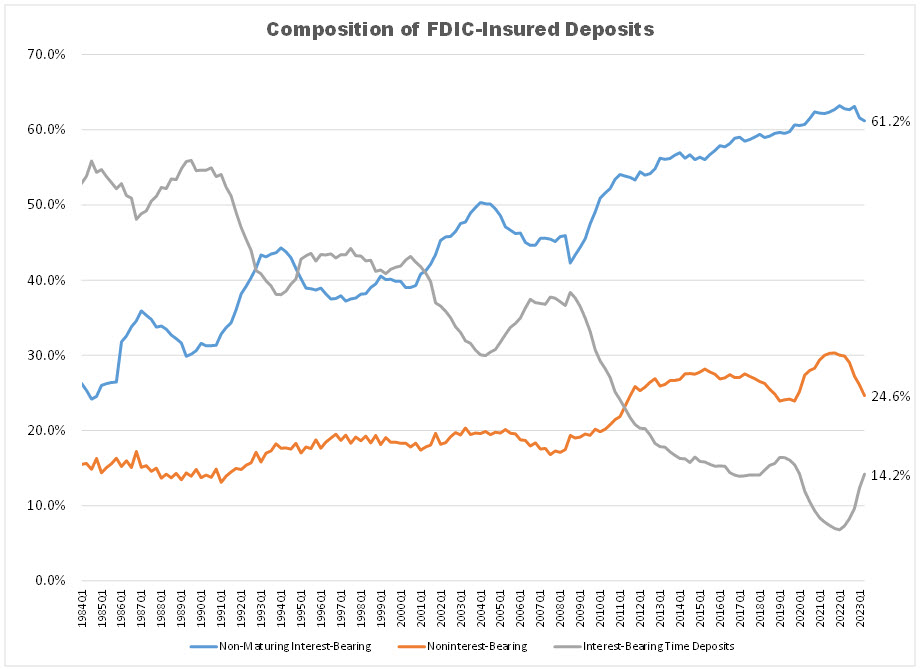

U.S. deposit composition has shifted dramatically. Aggregated data shows a steep decline in non-interest-bearing deposits in recent quarters. Banks and depositors now clamor together for time deposits, which some would have called a “dead product” just a few years ago. Looking at banks’ deposit composition, CDs have reclaimed more ground since 2022 — and gained more volume — than they have since the turn of the century.

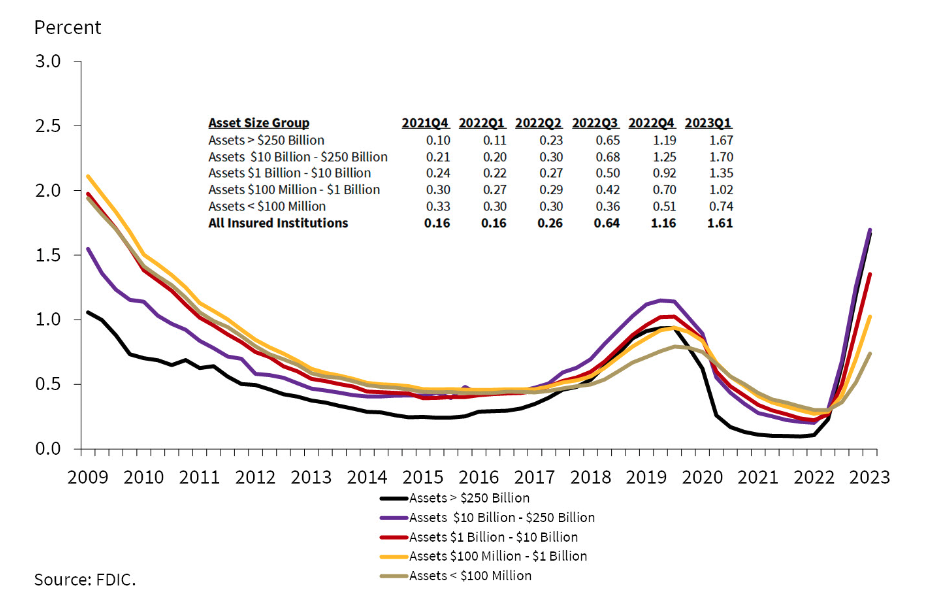

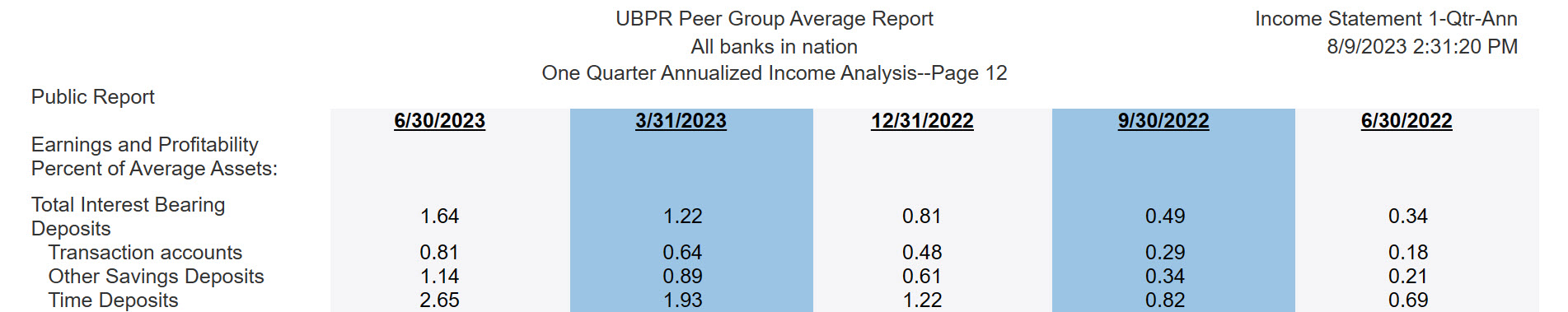

Take a look at the trends for cost of funds during the past six months. In just a year, total interest expense has climbed by more than 400 percent, according to second-quarter data from the FDIC. For example, interest expense on “Other Savings Deposits” are up nearly five and half times compared to a year ago.

Across the spectrum of asset sizes, cost of funds has exceeded or now flirts with levels not seen since 2009, especially for banks $1 billion and above.

These are dramatic increases in interest expenses. But are we finally there? Have we reached the top? The Fed Funds target is 5.25 percent to 5.50 percent, at the time of this writing. CME FedWatch, which forecasts the probability of rate increases or decreases by the Federal Reserve, currently indicates overnight rates are unlikely to fall below 4 percent until December 2024.

Rates may have peaked, but bankers should not hope for a return to the low-rate conditions of 2020.

Taking the pressure off

Banking circumstances would seem very dire if repricing the funding book on its own could derail profitability. Let’s take some pressure off that belief.

Low deposit prices do not correlate with high ROA. There are low-cost-of-funds (COF) and low-ROA banks. And, there are banks reporting interest expense between 3 percent and 3.5 percent — some of the highest in the industry — with ROAs above 3 percent. Analyzing Q2 data released by the FDIC, ROA only has a 2.8 percent R2 correlation to COF. That’s on a 0 percent to 100 percent correlation scale, where 0 percent means no correlation.

If COF correlated to ROA, we should see a tight cluster of dots around the regression line. Some high ROA banks with high fee income or revenues from specialty divisions would be clear outliers. Instead, the data shows the results below.

The value of volume

How could a bank with a high COF have a high ROA? Consider that the six-month U.S. Treasury yield is around 5.5 percent; any CD portfolio priced below 4.5 percent is creating a riskless 1 percent ROA. Most banks are just beginning to flirt with 4 percent on a 12-month, which provides an even higher ROA. That would put them near the middle of the pack for ROA when looking at the CD portfolio alone, all while operating with a 4.5 percent COF.

Obviously, arbitrage with treasuries doesn’t account for non-interest expenses, but banks also are not investing in treasuries if they can help it. Banks want deposits to fund loans. And that’s where the rubber hits the road with rising rates.

Similar to the used car business, the number of cars sold is a function of how many cars the business has in inventory, which in turn is determined by the pricing approach in buying them. If the owner said, “Inflation is up, but I will not pay 15 percent more for vehicles,” that’s too focused on one ingredient: Inventory cost. What if paying more would increase inventory and, thereby, profits? What if marginal revenue gains outpaced the higher marginal expense?

It’s the same for deposits made into loans. Banks can gain more from increased volume than they lose to modest rate increases. And sometimes, not making a marginal rate increase means the volume in your inventory is sufficient to deliver the profits you desire. Such a bank would have a low COF, they’re just missing an ingredient for a high ROA. Volume is the quieter partner in the banking business; unlike prices, it doesn’t make headlines.

Fortuitously, treasuries — and alternative funding like wholesale and brokered deposits — act as benchmarks for tradeoff between volume and price. With certificates booked at 4.5 percent needing no subsidization, banks have room to work with. The exciting question should be: How much ROA can the bank drive if it excels at both pricing and volume?

Obtaining volume

Bankers can know their preferred prices before they eat breakfast. Volume is where all the skill and art enter deposits, it’s what they will engage customers about in real time. What price will depositors feel is fair?

Plenty of popular tactics spiral out of control quickly. There’s lots of pressure for ad hoc exception pricing, and odd-term CD specials. The former bogs down staff and managers and trains customers to push harder for exceptions; they then tend to encourage other depositors to do the same. CD specials train customers to be deal shoppers.

Even the much-loved tiered offering based on dollar amount is not dynamic enough for today; some depositors may have been happy with a standard rate. Would you reduce a commercial loan customer’s rate by 1 percent without them negotiating for it?

Banks with deposit acumen have developed both a negotiation process and tiered packages to support that process. Together these widen deposit conversations away from price. Sometimes it’s the simplest things that matter. Depositors consider taking on a multi-hour process to move elsewhere for a CD that pays only a small amount more. And they do it thinking of percentage rate. Have you ever shown them the comparison in dollars between your 12-month CD and the competitors’ for the same term? There is a library of similar tools that staff need, and quickly.

Deposit success has become as much about negotiation as commercial loans. Staff need training and a roadmap, not a rate sheet, to reach that level of negotiation. The foundation for that process is the customer. Staff must learn about the person sitting in front of them. Are they sleepers, just curious, or a rate shopper? The best processes don’t wake the sleepers; they respect curiosity, and they negotiate effectively with the bargainer.

Banks achieve volume at the meeting place between depositors’ interests and those of the bank. It’s not available to those who choose arbitrary and unsophisticated approaches because they’re hyper-focused on price, which tacitly commoditizes the bank. Banks create value by combining features that tailor a financial fit between depositor and bank. That value creates differentiation and drives volume.

Neil Stanley is founder and CEO at The CorePoint.