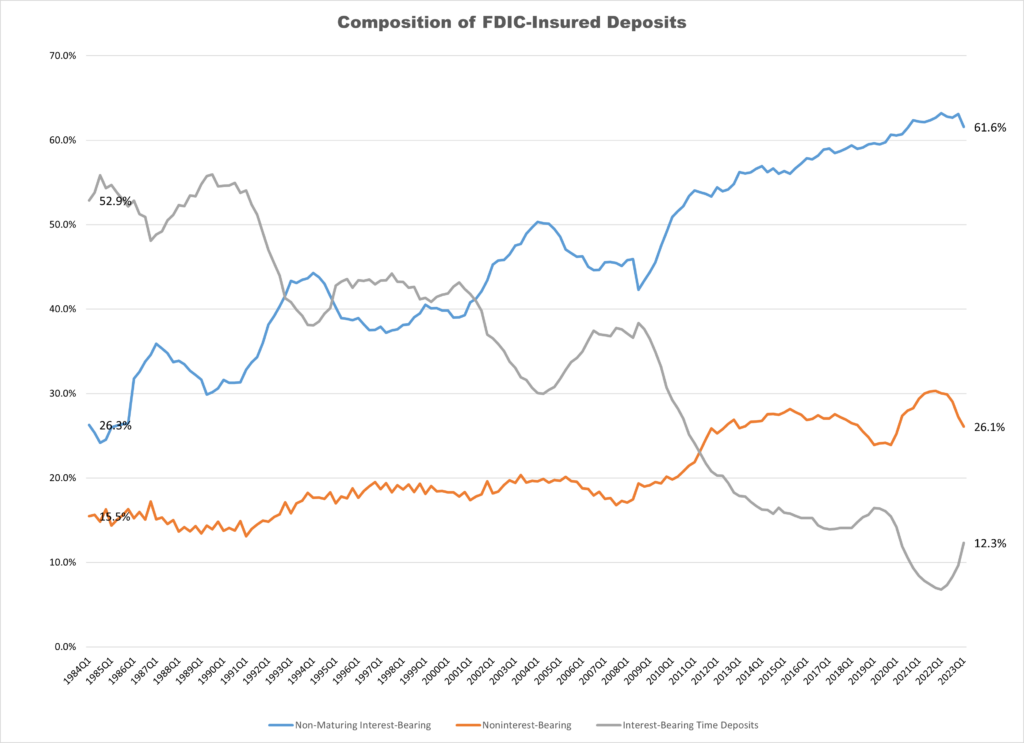

If bankers could choose a funding portfolio made up of deposits committed for a time, or deposits that could leave at any time, they’d choose the former. But, looking at the industry’s deposit composition during the last 30 years, it appears just the opposite. Certificates of deposits used to compose 55 percent of all bank deposits; now they’re down to just 12 percent.

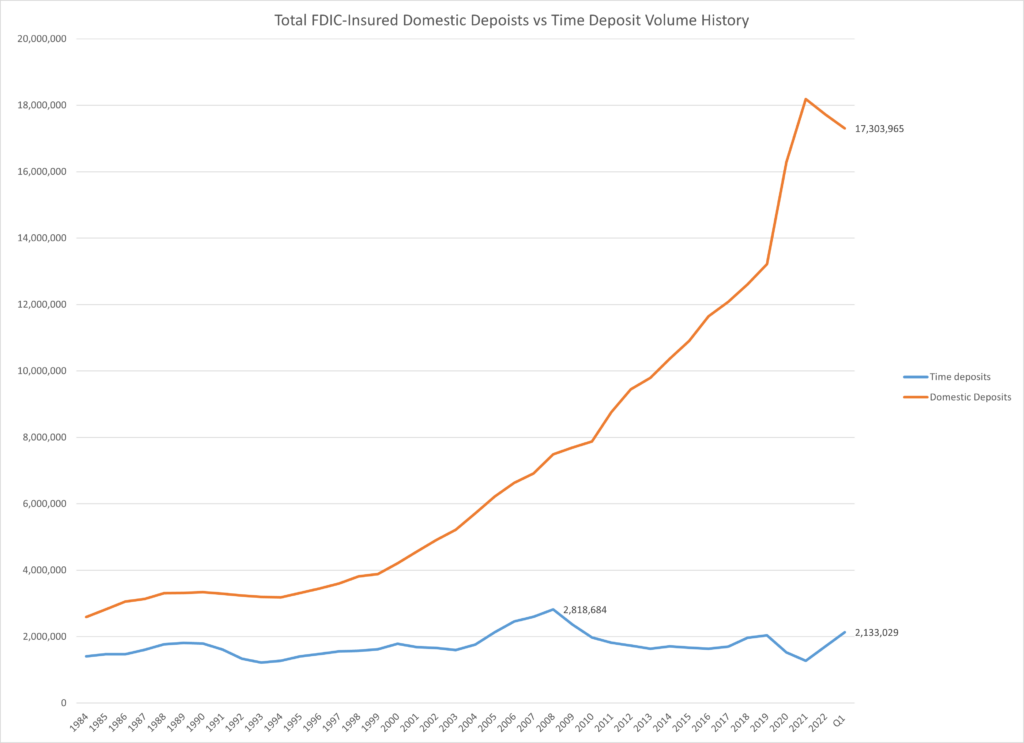

That’s not to say CDs didn’t have their good years. Before the financial crisis of 2008, they reached their 30-year high point of $2.8 trillion. Though that sounds impressive, total domestic deposits grew from about $4 trillion in 2000 to about $7 trillion in 2008. During that same time, CDs grew by just $1 trillion, having fallen to less than 40 percent of the industry’s funding — and those were the good years.

Comparing 2008 to 2023, banks now hold nearly 2.5 times more deposits ($17.3 trillion) while time deposits recently made it past the $2 trillion mark, they continue to hover around that level, as they have since 1985.

If our asset-liability logic says banks would generally prefer term deposits, what dethroned the CD? Bankers already know the common answers: Interest rates and/or depositor preference. Let’s see if those reasons stand up to scrutiny.

Falling from favor

Industry veterans know something changed after the financial crisis when, for logical economic reasons, the Federal Reserve began the policies that dropped rates near zero. For 15 years there has generally been no safe, FDIC-insured option for depositors that offers returns above 1 percent. For most, there’s been little yield to be gained from agreeing to a term, so people parked cash in savings accounts, invested in the stock market, or tried cryptocurrency instead.

Did rates demotivate depositors from choosing time deposits? Absolutely. But by how much? Before monetary stimulus, CD growth for the industry already lagged behind non-maturing, interest-bearing accounts. Also, depositors have always considered rates, that’s not new. Why did the CD stagnate — while the DDA exploded — before 2008, when rates weren’t near zero?

If it were rates that dethroned CDs, then we should see similar declines in other time investments, such as U.S. Treasuries. But we don’t. U.S. Treasury bills and notes — looking at those of comparable duration to CDs — have exploded to more than $17.7 trillion. That’s a nearly 7-fold increase from the $2.6 trillion on the Treasury’s books in May 2003.

People are investing in time investments in similar volumes and with similar growth to total domestic deposits; they’re just not doing it at banks.

The missing feature

If rates have not shut down growth in CDs, then it must be depositor preference. But why wouldn’t people want a CD?

Certificates of deposit and US Treasury bonds are competitors for informed investors, and people appropriately prefer treasuries. Both offer a coupon structure paying a fixed annual percentage yield for a fixed term, but they have key structural differences. When people need to access their money, U.S. Treasuries offer investors they can sell it — without a fixed penalty — to a market for its value. When sold to the market, they also can provide a much higher return than the coupon, primarily if sold when rates are down.

CDs cannot be sold for liquidity. While they can be withdrawn, the best an investor can hope for is to access the capital without penalty. For CDs, yield is yield; even when the financial institution would benefit from cashing them out, they do not increase in value.

Now, strip them of their names and set their features side by side. Don’t look at CDs as a bank product; look at them as a wise investor selecting for the bond portfolio. Which coupon would you choose? One with a fixed penalty and no possible upside? Or one with liquidity options, no fixed penalty, and significant upside potential depending on rate movement? No informed investor chooses the first investment over the second; it simply has far more options for an unknown future.

The structure of Treasuries explains CDs’ relative decline in the marketplace over the past four decades. It also suggests how CDs can reclaim their time-worn crown: People want a CD they can withdraw early, and they will accept market-value risk to gain options.

Finding a solution

Some banks have begun offering no-penalty CDs because they have a more attractive structure to depositors. Banks, however, cannot offer them as the core of their funding strategy because there’s no friction for depositor attrition. Why offer a term product that provides the bank no protection against rising rates? That’s what they’re for.

On the depositor side too, no-penalty CDs are for people who want a fixed APY, one usually lower than a traditional CD, and who may need access to the money. With rates on savings accounts and money market accounts, though, most people just opt for fully liquid accounts. If depositors want a term product, they’re opting for a treasury because there’s a market for them rather than a fixed penalty.

Some leaders have taken their offerings in the other direction. Instead of no-penalty CDs, they are increasing the penalty, some by 10 times. If that sounds backwards, it should. In rising rates, holders of US Treasuries stay in their investments if they can, because of declines in the market value; they stay even when not locked in by a penalty. In declining rates, a US Treasury that booked at a higher rate is more valuable to the holder. If the treasury were a bank, it should welcome the opportunity to close it.

It’s the market value of Treasuries that makes them more efficient for investors. Banks don’t need bigger penalties; they need to create the same kind of market for their CDs. The CD relationship is then no longer a zero-sum game. Banks’ CDs then provide more options to depositors, and banks’ cost of funds remain protected by the market value of their CDs. The market-maker then can define the CD’s value, which it bases on its own asset-liability strategy.

Imagine if people could buy the same product from their bank that they now buy from the US Treasury by the trillions. No more dealing with the “amazing” customer service of the federal government, no more moving money back and forth, and all of it managed within the bank’s convenient mobile app.

Neil Stanley is founder and CEO at The CorePoint.