Editor’s Note: The following is excerpted from a white paper published jointly by Willary Winn LLC, Winthrop & Weinstine and Eide Bailly. Find the complete document visiting any one of their respective websites.

The recent trend of credit unions buying banks has become one of the hot topics in the industry. While the number of actual transactions is quite small relative to the number of mergers and acquisitions that take place each year, the trend has been a featured item at recent financial institution industry conferences. By way of comparison, we note that through Sept. 30, 2019, there have been 18 deals either completed or with expected completion dates in 2019 or 2020 in which a credit union buys a bank. This compares to 298 bank-to-bank transactions either completed or with expected completion dates in 2019 or 2020 and 111 approved credit union-to-credit union mergers.

A credit union purchasing a bank is a relatively complex undertaking, and the purpose of this article is to provide community banks with the information they need to ensure both buyer and seller are making informed decisions.

Strategic Considerations

When evaluating offers for the bank, shareholders need to ensure that they are comparing the bids on an “apples-to-apples” basis. An all-cash bid from a credit union could be the highest gross offer, but the bank should consider the possible income tax consequences, as well as the legal and regulatory costs arising from the transaction to determine the amount it will receive on a net basis. Finally, a seller should consider the net proceeds it would receive for assets the credit union is unwilling or unable to purchase.

When evaluating offers for the bank, shareholders need to ensure that they are comparing the bids on an “apples-to-apples” basis. An all-cash bid from a credit union could be the highest gross offer, but the bank should consider the possible income tax consequences, as well as the legal and regulatory costs arising from the transaction to determine the amount it will receive on a net basis. Finally, a seller should consider the net proceeds it would receive for assets the credit union is unwilling or unable to purchase.

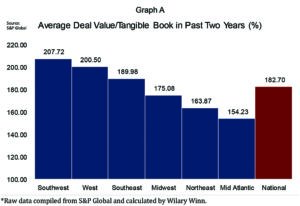

Graph A shows the average deal value/tangible book value over the previous two years for bank-to-bank acquisitions in both the nation and by region. While the focus of this article is on credit union-to-bank acquisitions, there is limited publicly available information for these transactions. Recognizing the differences between credit unions and banks and the potential tax and regulatory costs associated with the differing deals, we nevertheless believe understanding and utilizing current bank-to-bank deals in the marketplace can be a useful way to benchmark an offer submitted by a credit union.

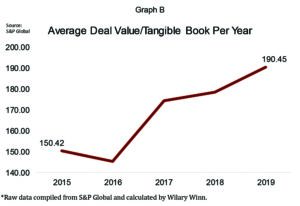

We note that the average deal We note value/tangible book value for bank-to-bank acquisitions in the marketplace has increased considerably over the past five years as shown Graph B.

We believe the increase in prices in 2018 and 2019 are due to increased competition for customer deposits, easing bank regulations, lower corporate tax rates, and the hunt for digital capabilities. Going forward, it is difficult to predict whether this trend will continue. The industry is facing potential NIM compression resulting from the reduction in the Federal Funds rate, political uncertainty entering an election year, and the ongoing uncertainty regarding the future health of the economy.

We believe the increase in prices in 2018 and 2019 are due to increased competition for customer deposits, easing bank regulations, lower corporate tax rates, and the hunt for digital capabilities. Going forward, it is difficult to predict whether this trend will continue. The industry is facing potential NIM compression resulting from the reduction in the Federal Funds rate, political uncertainty entering an election year, and the ongoing uncertainty regarding the future health of the economy.

Tax and higher legal costs aside, a community bank might be willing to sell to a credit union because the credit union is willing to pay cash while a community bank might want to merge with the selling shareholders, thus trading one form of illiquid bank stock for another. In addition, the bank should evaluate the bidder’s ability and willingness to serve the bank’s customers, retain its employees, and to ensure a smooth transition in the community in which the bank operates.

Cultural considerations are very important. Questions to consider include:

- Does the acquired institution have similar goals and values? We believe this will often be the case as credit unions and community banks are both generally focused on serving their communities.

- Does the to-be-acquired institution have a similar business model and operating strategy?

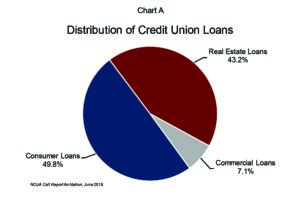

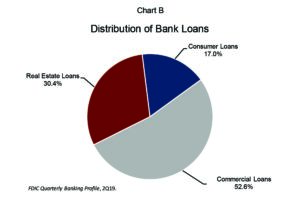

This very often might not be the case. Credit unions generally focus on consumer and residential real estate loans, while most community banks focus on commercial real estate loans and other business loans. This is reflected in the following Chart A and Chart B.

One of the reasons a credit union might want to acquire a bank is to obtain specific expertise. A common example is commercial lenders. This can create two complications. The first is ensuring the credit union can retain the loan officers because, in our experience, the loan customers are

One of the reasons a credit union might want to acquire a bank is to obtain specific expertise. A common example is commercial lenders. This can create two complications. The first is ensuring the credit union can retain the loan officers because, in our experience, the loan customers are

very loyal to their loan officer. If the loan officer does not stay, the credit union could have difficulty retaining the customer and its deposits. The second complication is that commercial real estate and acquisition, development, and construction loans often comprise a significant portion of a bank’s balance sheet. These loans can be very difficult to evaluate, and an acquiring credit union would either need to possess the expertise to perform due diligence on these loans prior to the acquisition or outsource the work. Finally, we note that a credit union is limited to the amount of commercial loans it can hold on its balance sheet. A federally insured credit union has an individual lending cap for commercial loans to one borrower equal to the greater of 15 percent of net worth or $100,000, plus an additional 10 percent of the credit union’s net worth if the amount exceeding the 15 percent is fully secured. In addition, a federally insured credit union has an aggregate cap on net member loan balances equal to the lesser of 1.75 times its actual or required net worth.

Tax Consequences

A bank can be one of two kinds of taxpaying entities – an S-corporation or a C-corporation. Whether a bank is one versus the other can have major tax effects on the transaction. The sale of an S- corporation bank can result in taxes at the shareholder level only, whereas the sale of a C-corporation bank can result in taxes both at the bank level and to the shareholders. The form of the acquisition agreement also affects the taxes that will arise from the transaction. An acquisition can be structured as a taxable “purchase & assumption” deal, otherwise termed as a taxable asset sale, where the buyer purchases the bank’s assets and assumes the bank’s liabilities – consisting mostly of the deposit accounts. Alternatively, if the buyer is another bank, bank holding company, or other taxpaying entity, the transaction can be structured as the sale of stock and avoid the “double” taxation. Finally, a bank can also offer its stock as consideration to the selling shareholders, which could result in no tax at the time of the sale provided it is properly structured.

A bank can be one of two kinds of taxpaying entities – an S-corporation or a C-corporation. Whether a bank is one versus the other can have major tax effects on the transaction. The sale of an S- corporation bank can result in taxes at the shareholder level only, whereas the sale of a C-corporation bank can result in taxes both at the bank level and to the shareholders. The form of the acquisition agreement also affects the taxes that will arise from the transaction. An acquisition can be structured as a taxable “purchase & assumption” deal, otherwise termed as a taxable asset sale, where the buyer purchases the bank’s assets and assumes the bank’s liabilities – consisting mostly of the deposit accounts. Alternatively, if the buyer is another bank, bank holding company, or other taxpaying entity, the transaction can be structured as the sale of stock and avoid the “double” taxation. Finally, a bank can also offer its stock as consideration to the selling shareholders, which could result in no tax at the time of the sale provided it is properly structured.

Because nearly all states do not permit a credit union to purchase the stock of a commercial bank, an acquisition of a commercial bank by a credit union generally must be structured as a taxable asset sale, where the credit union purchases the bank’s assets and assumes the bank’s liabilities. In this case, the bank charter is left as a shell corporation containing the cash purchase price paid by the credit union. The shell corporation is then likely liquidated with the cash proceeds distributed to the selling shareholders.

As a general rule, a bank buyer prefers to structure an acquisition as a taxable asset sale, because the buyer can amortize and deduct the premium paid for income tax purposes, generally over a 15-year period. The net present value of the deduction of the premium is approximately 22 percent to 25 percent, decreasing the after-tax purchase price for the bank buyer. Of course, a credit union cannot reap the buyer’s tax benefits of a tax-deductible premium. It must undertake the acquisition as a taxable asset sale simply because it cannot own bank stock in most jurisdictions.

A taxable asset sale of a C-corporation bank generally results in “double taxation.” Any premium paid on the deal will first be taxed at the corporation level, currently at a 21 percent federal tax rate, plus the applicable state tax rate. After the corporation pays that tax and distributes the remaining sales proceeds to the shareholders, the shareholders will again pay tax on their capital gain from liquidating their stock investment.

We note that any net operating loss or tax credit carryforwards available to the C-corporation can offset the gain from a premium received. Because of the double taxation, most C-corporation sales transactions are structured as stock sales.

On the other hand, most S-corporation sales transactions are structured as taxable asset sales because there is only a single layer of tax on a premium paid. The taxable gain associated with a premium is not taxed at the corporate level. It instead flows through to the shareholders as a taxable gain and in turn increases their stock basis. We note that this tax advantage applies only to S- corporation banks that have made their S- election more than five years before the sales transaction. If the selling bank had not yet reached its fifth anniversary as an S-corporation, it would potentially be subject to the IRC Section 1374. A portion or all of the premium could be subjected to a 21 percent federal corporate level tax, as well as potentially a state-level corporate tax depending on the circumstances. Thus, an S-corporation that recently made its S-corporation election could also be subjected to the “double tax” penalty of a corporation selling its assets, versus the corporation’s sellers selling their stock and paying a single layer of income tax.

If state laws permit a state-chartered credit union to merge with a bank and it does so, the transaction is treated for tax purposes as a taxable disposition of assets, regardless of the fact that the form of the transaction was a merger. This is because a credit union is exempt from federal income tax and the transaction thus falls under IRC Section 501(c)(14). IRC Section 337(b)(2) and Treasury Regulation 1.337(d)-4 outline the rules that apply when a taxable entity, like a bank, transfers all or substantially of its assets to a tax-exempt entity like a credit union. It is a “deemed sale” of the taxable entity’s assets at their respective fair market values with the same result as a taxable asset sale. Further, a credit union does not issue stock to the selling shareholders, so the merger transaction cannot be structured as a tax-free stock-for-stock exchange.

There are other nuances that go into calculating the gain or loss from taxable asset sales. The purchase price is spread amongst the assets of the selling corporation according to the assets’ respective fair market values, pursuant to IRC Section 1060. Depending on the schematics of the purchase price allocation, there could be opportunities for a selling S-corporation to realize an ordinary loss on some assets (tax benefit at the higher ordinary tax rates) and increase the capital gain portion of the transaction (premium/goodwill), with lower rates on capital gains for the S-corporation’s shareholders. A C-corporation pays ordinary taxes and the capital gain income at the same rate; thus, purchase price allocation schematics generally present less of a planning opportunity for C-corporations.

Legal and Regulatory Issues

There are a number of legal and regulatory issues that must be considered in connection with a potential acquisition of an FDIC insured bank by a credit union.

As we noted earlier, in the majority of cases a credit union cannot own or acquire the shares of the bank. To be more specific, a federal credit union cannot purchase the shares of a community bank or merge with it. A few states, Florida being the prime example, explicitly allow a state-chartered credit union to merge with a bank. Other states forbid the transaction just as the NCUA does, and the majority of state statutes are silent on the matter.

As such, the legal structure utilized in a credit union’s acquisition of a bank is an agreement for the credit union to purchase all the assets and assume all the liabilities of the bank. This means that there must be an individual transfer of each asset, an assumption of each liability and an assignment of any intangible or collateral rights at closing. This creates a more complex and burdensome legal process to ensure all the required legal documents necessary to complete the transfer of each asset and the proper assumption of each liability are prepared and executed. This process is more complex than what occurs when the transaction is structured as a purchase of stock or merger.

Any transaction where a credit union purchases a bank must include a definitive purchase and assumption agreement setting forth the key terms and conditions of the transaction. This agreement must be the result of an arms-length negotiation and both the credit union and the bank have duties to protect their respective interests. These fiduciary duties fall to the officers and directors of the credit union and the bank.

Directors and officers of a bank want to maximize shareholder value as part of any sale and minimize any post-closing risk or risk that the sale will not be consummated. This requires the bank to negotiate a definitive agreement that limits the scope of representations and warranties given, reduces the conditions to closing, and eliminates post-closing liabilities. Because directors and officers of a bank ultimately report to the shareholders of the bank, those individuals are often intimately involved in negotiating, reviewing, and approving any agreement. This means that banks will want a detailed legal agreement clearly setting forth the specific representations, warranties, and covenants being made as part of the transaction.

Credit unions have generally used more simplified agreements in credit union to credit union mergers, in part, because the two credit unions become one and no cash is being paid out of the acquiring credit union. Further, a credit union might be less concerned about obtaining representations and warranties or incurring post-closing liabilities in a merger of two credit unions because it retains the capital of the credit union being merged. However, because a bank purchase is an all cash deal, it is important for credit unions to obtain appropriate representations and warranties regarding the condition and status of the bank and have some form of recourse post- closing to protect the credit union from risk of loss due to a breach of the definitive agreement, fraud, or other damages. This requires credit unions to spend more time, care, and legal expenses negotiating and finalizing a definitive agreement than in a typical credit union to credit union merger.

One final difference for both banks and credit unions in any legal agreement for the acquisition of a bank by a credit union concerns the scope of the operating covenants that govern the operation of the selling bank from the date a definitive agreement is signed until closing. Typically, any bank sale will include negotiated operating covenants restricting the selling bank from taking any extraordinary actions from the date the definitive sale agreement is executed through the date of closing. These operating covenants are heavily scrutinized by federal bank regulators to ensure that the acquiring entity is not exerting extraordinary control over the bank it intends to buy prior to actually owning the bank. Typically, the NCUA is more relaxed about a buying credit union’s ability to control bank operations prior to the closing date. This creates an issue of prior control that the bank’s officers and directors need to recognize and address appropriately with the banks. This results in the need for careful negotiation of such covenants in any definitive agreement.

Both the credit union and the bank will be required to file regulatory applications as part of a credit union acquisition. This results in different regulatory considerations for both buyer and seller than what one sees in a bank to bank transaction or a credit union to credit union merger.

Banks, of course, can be state- or nationally-chartered. State-chartered banks are regulated by the state in which they were formed and by the FDIC – the primary insurer of their deposits. Nationally-chartered banks are regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the FDIC. In addition, state chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve are federally regulated by the Federal Reserve as its primary federal regulator and also by the FDIC. A bank considering a sale to a credit union must file with its primary federal regulator and applicable state regulator.

Once the purchase and assumption is completed, the bank will be a shell charter with minimal to no assets remaining in the organization. As such, for a state-chartered bank, both the federal and state banking regulators will require that the former bank dissolve. In the case of a national bank, the OCC will require that the shell charter be merged into an affiliated entity. This will require a special regulatory application to the applicable federal bank regulator. Additionally, if the bank being sold is a state-chartered bank, the appropriate state banking agency will require an application in connection with the sale. Considerations for each of the FDIC, OCC and Federal Reserve are listed below.

Federal law explicitly requires prior written approval from the FDIC before any insured depository institution may transfer FDIC insured deposits to a “noninsured bank or institution” – this includes credit unions because credit union deposits are insured by the NCUA and not by the FDIC. We note this applies even for the sale of a branch by a bank to a credit union if the credit union assumes the deposits of that branch. We note that the FDIC recently indicated that is considering the implications of credit unions buying banks.

The FDIC will require its own interagency merger application to be filed with it even though the sale to the credit union is a purchase and assumption transaction. In fact, an acquisition of a bank by a credit union, regardless of the bank’s primary federal regulator, will require FDIC approval as the FDIC is the only federal bank regulator that can act on the assumption of an FDIC insured bank’s deposits by a credit union. If the FDIC is not the primary federal regulator for the bank, the FDIC will work closely with the OCC or the Federal Reserve (as the case may be) throughout the application review process.

Similar to the application submitted to the NCUA, the FDIC application will require a detailed description of the proposed transaction and copies of the relevant transaction documents. Additionally, the FDIC requires a description of any non-conforming or impermissible assets that the credit union may not be permitted to retain – as noted above, this would include certain types of deposits or non-conforming loans that cannot be held by a credit union. As part of the application, a description of the method of divestiture or disposal and anticipated time period must be submitted to the FDIC. Finally, in reviewing applications which contemplate a credit union as the surviving entity, special consideration is given to the disclosures made to depositors regarding the change in deposit insurance.

Due to the requirement from the NCUA that the transaction be structured as a purchase and assumption transaction, the OCC requires a two-step process when a credit union seeks to acquire a national bank. The first step is to receive approval for the sale of substantially all the assets and

assumption of substantially all the liabilities of the national bank. The second step is to receive approval to merge the then uninsured national bank with and into its holding company. The filings required for both steps can be filed simultaneously with the OCC along with a transmittal letter summarizing the process.

A unique complication can occur if the state where a national bank’s holding company is incorporated in does not provide explicit authority for the merger of an uninsured national bank with and into a state corporation. This will require a state-by-state analysis of permissibility. If this is the case, the national bank may need to include the additional step of forming a subsidiary and first merging the then uninsured national bank into the subsidiary with the subsequent merger into the holding company to immediately follow or finding some other avenue to merge the shell bank out of existence. As with the streamlined process first outlined, the formation of the operating subsidiary can occur all in one filing along with the steps outlined above.

Conclusion

The acquisition of a bank by a credit union is a relatively complex transaction involving multiple regulatory agencies, federal and state income taxes, and multiple strategic considerations. We hope this white paper has helped readers better understand the ramifications that could arise in

undertaking a deal of this type.

The issues addressed in this white paper are complex and are based on general information and examples only. Readers should not rely on the information contained in this paper regarding potential transactions without first seeking advice, input and comments from their independent accountants, attorneys and primary regulators before undertaking the such a transaction. Readers are strongly encouraged to seek such independent advice as the specific facts and circumstances in each particular transaction could lead to different accounting, tax, legal and regulatory interpretations than those described herein.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Douglas Winn

Winn co-founded Wilary Winn. His primary responsibility is to set the firm’s strategic direction. From an idea in 2003, Wilary Winn has grown into a national presence with financial institution clients located across the United States. Wilary Winn’s clients include more than 250 community banks, 67 of which are publicly traded and over 250 credit unions, including 40 of the top 100.

Winn is a nationally recognized expert regarding accounting and regulatory reporting for financial institutions and speaks regularly at industry conferences. He has led seminars sponsored by the AICPA, the FDIC, the FFIEC, the NCUA, and many of the country’s largest accounting firms. You can reach Doug at [email protected].

Anton J Moch

Moch joined Winthrop & Weinstine, P.A., in 2001 and is a shareholder practicing in the field of community banking and financial services. From its inception, Winthrop & Weinstine has specialized in representing banks and financial institutions and has deep bench strength and extensive experience in banking law with a multi-practice approach allowing it to provide a full range of services, including community banking, governance, mergers and acquisitions, enforcement and regulatory compliance, securities, trust services, commercial lending, creditors’remedies, insurance, tax, corporate, real estate, employment, intellectual property, antitrust, and specialized financial services litigation.

Moch’s in-depth experience and strong relationships with community banks allows him to work with and advise senior officer teams, board of directors and ownership groups on a broad and varied set of issues, including, mergers and acquisitions, branch acquisitions, corporate restructuring, expansion strategies, organic growth strategies and activities, De Novo charters and De Novo branching issues and the sale of financial organizations to third parties. Mr. Moch also has extensive experience regarding compliance and regulatory issues, routinely assists community banks with regulatory filings and applications and works in close connection with his contacts at federal and state regulatory agencies. You can reach Tony at [email protected].

Paul Sirek

Eide Bailly is a top 25 public accounting firm with more than 700 community financial institution clients. Mr. Sirek’s focus at Eide Bailly is on the financial institutions industry. He provides management consulting, tax planning, and tax compliance services to financial institutions ranging in size from less than $50 million to more than $1 billion. He conducts tax research projects, and he assists financial institutions with merger and acquisition issues including tax structuring of transactions and the regulatory application process. Paul also assists bank holding companies and financial institutions with regulatory filings including FR Y-9C, FR Y-9LP, and FR Y-9SP reports.

Sirek is attentive and very responsive, promptly replying to inquiries and providing a high level of customer service. He communicates current tax developments to clients and staff so they are up to date on requirements, and he consults with financial institutions, as well as their shareholders, on S- corporation conversions and S-corporation planning issues. His goal is to provide clients with the tools they need for growth and success. You can reach Paul at [email protected].