It is tempting to believe that a low cost of funding is synonymous with success. Banks must constrain cost, but it’s not sufficient to achieve maximum profitability. The highest performing institutions achieve both funding volume and spread.

Many banks have held the line on funding costs — perhaps to their own detriment, according to FDIC data from the first quarter. Leaders know intellectually that they can’t save their way to prosperity, unless they have low cost of funding and significant, sustainable deposit growth, a rarity among banks today. Many now turn to a simplistic tactic: Delaying rate increases while allowing deposit relationships to decay.

Bankers correctly have learned that repricing the entire book to gain a marginal amount of new funding is typically damaging to their net income. But, is it reasonable to expect a cost of funds hundreds of basis points below the current Fed Funds rate of 5-plus percent?

Executives who focus single-mindedly on cost of funds have missed the exit ramp, and it does not bode well for their organizations. With some art and some science, banks can de-commoditize deposits by segmenting deposit offers in more robust and differentiated ways than those deployed decades ago.

Improved sales processes — and training for frontline staff that has not been imperative since 2009 — can differentiate a bank and bring in profitable funding, though higher-priced, without the detrimental impact of repricing the entire book with across-the-board rate increases.

Instead, many bankers are stuck in “delay and decay” mode.

Who wins in delay and decay?

In the first quarter of 2023, the median on the Uniform Bank Performance Report for all banks for CD interest expense was 1.94 percent. However, when you analyze the industry’s total CD interest expense divided by the average volume of CDs held during the quarter, you get something very different: 2.99 percent. This means that the average CD holder earned 2.99 percent in the first quarter on their FDIC-insured time deposits while 50 percent of banks had average portfolio yields below 1.94 percent.

In March, BankBeat covered how averaging the rate offerings distorts industry perceptions of interest expense because rate offerings do not report volume. From fourth quarter 2021 to third quarter 2023, funding prices seemed flat. All the while the average yield on deposit products like CDs was doubling.

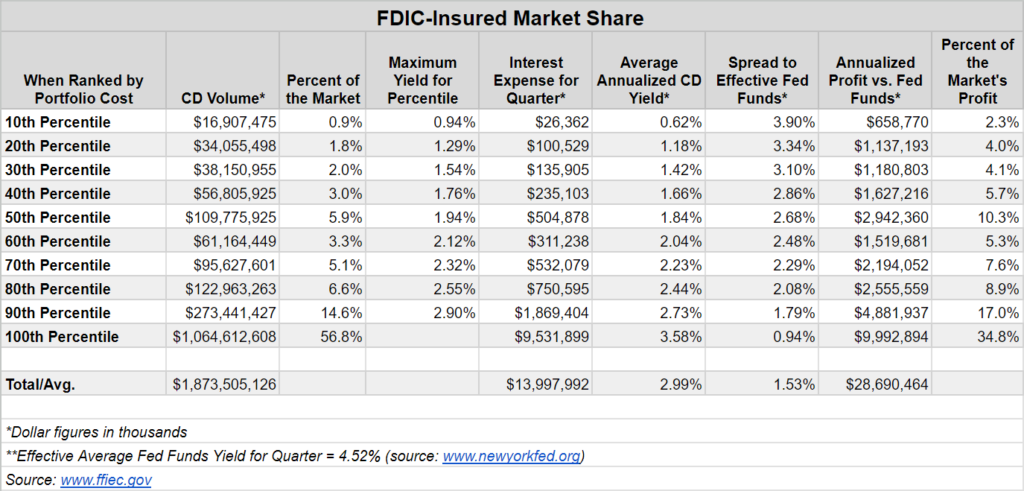

The table below reports the 10th percentile among institutions — those with low interest expense on their CDs — reported a 0.94 percent average yield on time deposit, whereas those in the 90th percentile reported 2.9 percent. The 0.94 percent cost of funding on CDs probably sounds fantastic, but a better word would be fantasy. Those in the 80th percentile or above commanded 78 percent of the volume in the time deposit market. The 10th percentile attracted miniscule volume, by comparison, at that yield (see chart below).

This data clearly demonstrates the miserly approach to depositors taken by the 10 percent of banks with the lowest cost of funds below 0.94 percent. They averaged 0.62 percent yield on CDs too. But they had a miniscule volume — only 0.9 percent of the industry.

The 10 percent of banks that garnered that impressive spread to Fed Funds of 390 basis points only realized 2.3 percent of the CD-market’s profit, according to a proxy calculation for Funds Transfer Pricing. (I used the Effective Fed Funds rate as a proxy for FTP because aggregated data does not include maturity data.) Using the same calculation, we see that 35 percent of the market’s profit belongs to those at the top, with those banks willing to reduce their spreads having an average yield on CDs of 3.58 percent. Clearly, these aggressive rate payers have attracted a dominant market share, with 56.8 percent of the industry’s volume.

Volumes at the lowest possible cost

Leaders should aim for a Goldilocks scenario where interest rates are put in proper perspective: To produce motivated depositors for significant volumes while managing a material profit spread for the institution. It’s not about casually increasing deposit interest rates. Neither ultra-low rates that fail to motivate deposit volume, nor ultra-high rates that make profit margins trivial, are acceptable.

Insisting on insured-deposit spreads upwards of 300 basis points is harmful, especially in a free market where aggressive competitors easily poach funds. Banks who pursued that strategy abandoned depositors who sought reasonable prices. Those customers now bank at institutions willing to pay relatively higher — yet still profitable — deposit rates.

But, before you suggest that competitors paying higher rates must be using a loss-leader approach, consider where the Fed Funds rate is today, having marched upward to 5.25 percent. They can invest newly acquired short-term funds, and any deposit booked at 5 percent or less needs no subsidization. They are clearly not loss leaders. Not only are the aggressive deposit rates observed today generally under wholesale funding costs, but they typically offer the opportunity to invest these funds in a modest but attractive risk-free spread.

Better approaches needed now

Remarkably, many frontline bankers seem unaware that a dollar from one depositor is no more or less valuable than a dollar from another depositor in terms of its potential to be invested or loaned out. If banks seek maximized profits, they must recognize that all deposit dollars can be invested in the same pools of potential loans and investments.

Profit maximization does not differentiate between customers and non-customers or depositors in one market or the other. It does differentiate based on size of account because there are cost efficiencies in getting larger relationships or because of relatively smaller costs arising from servicing these accounts. The key is to let the sleepers sleep, show respect to the curious, and negotiate skillfully with the rate shopper whether they are a current or prospective client.

The time has come for bankers to appreciate and embrace the need for more robust engagement with depositors. Banks need to drop erroneous assumptions about relationship pricing and hot money which pits them against depositors in a game of chicken.

Rightly, leaders should read that and think, “But we can’t just reprice the entire book.” Banks need the tools to manage both volume and pricing across the organization.

Executives and board members should begin by ensuring that their frontline is equipped, empowered, trained, and constantly coached on how to negotiate a deposit offering. Like commercial lenders, they need to work dynamically rather than relying on static rate sheets. They need to read the situation, and the depositor sitting in front of them, and navigate the discussion with standard pricing as the starting place. Then, promotional specials follow as necessary, followed by negotiated options that demonstrate flexibility based on competitive interest rates and tools that display competitive alternatives. Staff also need a last and best offer, when necessary, to retain depositors at a price point that’s mutually beneficial to the financial institution and its customer.

Without an upgraded approach, depositors will eventually conclude there’s a disconnect at their bank between rhetoric and behavior. Often that means they will move their money somewhere else. Nothing in your organization’s income statements will increase more this year (on a percentage basis) than interest expenses. Banks’ success will become even more heavily dependent on a coherent, effective, and efficient pricing strategy that achieves an oversized portfolio simultaneously with an oversized margin.

Neil Stanley is founder and CEO at The CorePoint.